On Wabi-Sabi Weekends, I post excerpts from my book, Simply Imperfect: Revisiting the Wabi-Sabi House.

“It is common now to hear people say of such and such a piece of country or suburb: ‘Ah! It was so beautiful a year or so ago, but it has been quite spoilt by the building.’ Forty years back the building would have been looked on as a vast improvement; now we have grown conscious of the hideousness we are creating, and we go on creating it.”

—William Morris

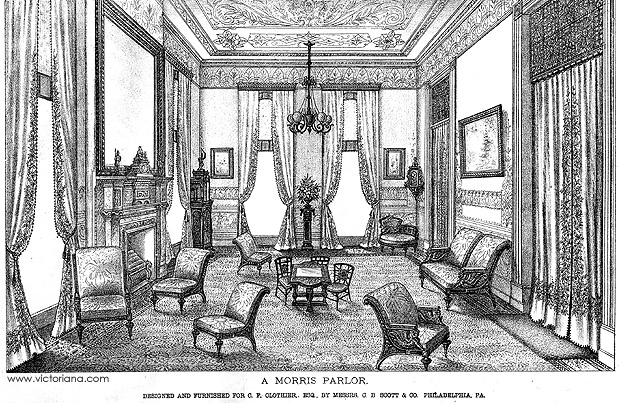

Reacting to the clutter common in Victorian homes, William Morris advocated for clean, simple interiors.

The telegraph, railroads and steam power were accelerating everything and stuffy, brocaded Victorian parlors signaled wealth and status when William Morris began his campaign for a return to handmade quality and the death of inessential decoration.

Morris—a socialist whose naturally dyed, hand-printed wallpapers were ironically cherished by the robber barons—railed publicly and prolifically against the “swinish luxury of the rich,” ornamental excess (“gaudy gilt furniture writhing under a sense of its own horror and ugliness”) and the poverty of people who lacked creativity. “Have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” he said, in one of the most often-repeated lines in home decorating.

Morris urged his students and disciples to constantly seek beauty in life’s mundane details. “For if a man cannot find the noblest motives for his art in such simple daily things as a woman drawing water from the well or a man leaning with his scythe, he will not find them anywhere at all,” he said. “What you do love are your own men and women, your own flowers and fields, your own hills and mountains, and these are what your art should represent to you.”

Saying that a well-shaped bread loaf and a beautifully laid table were works of art as great as the day’s revered masterpieces, Morris’s successor as the Arts and Crafts leader, W.R. Lethaby, said that modern society was “too concerned with notions of genius and great performers to appreciate common things of life designed and executed by common people.”

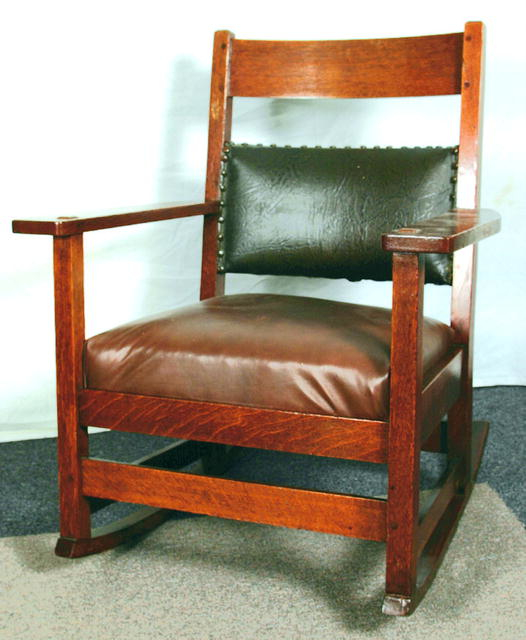

As the leading spokesman for the American Craftsman movement, which evolved from England’s Arts and Crafts, Gustav Stickley brought simple, solidly made furniture to the American masses at the end of the 19th century.

Stickley employed “only those forms and materials which make for simplicity, individuality, and dignity of effect.” He and his family lived in a simple log cabin, of which he wrote: “First, there is the bare beauty of the logs themselves with their long lines and firm curves. Then there is the open charm felt of the structural features which are not hidden under plaster and ornament, but are clearly revealed, a charm felt in Japanese architecture.”