On Wabi-Sabi Weekends, I post excerpts from my book, Simply Imperfect: Revisiting the Wabi-Sabi House.

“The essence of education is not to transfer knowledge; it is to guide the learning process, to put responsibility for study into the students’ own hands.”—Tsunesaburo Makiguchi

I went to Japan to learn more about wabi-sabi. I found it in the crowded, twisted alleyways of Tokyo’s Asakusa district, where I was always lost and strangers would walk me to my destination if they didn’t speak English. I understood it every time I watched a store clerk carefully wrap a jar of pickles in pretty paper, turning it into a small moment of celebration. I felt it when my host or hostess would turn my shoes around to face the door, so they would be easier to slip into when I left.

I feasted on wabi-sabi. In Japan, simple food—fish, rice, vegetables, seaweed and vinegar—becomes a visual feast, honoring the guests, the food, the dishes and even the utensils. There’s nothing more beautiful than pan-seared hake’s golden-brown edges picking up the rusty flecks of the platter it’s on or five thin slices of raw tuna and a dab of bright green wasabi fanned on an opalescent shell-shaped plate. On a hot summer day, a smooth, thin square of chilled tofu (hiyayakko), floating on half-melted ice chunks in a shallow bamboo bowl, is sublime.

Greek writer Lafcadio Hearn, who explored late-19th-century Japan extensively, described the Japanese culture as having “an ethical charm reflected in the common life of the people.” According to Hearn, “the commonest incidents of everyday life are transfigured by a courtesy at once so artless and so faultless that it appears to spring directly from the heart, without any teaching.” That generous attention to the moment, so prevalent throughout Japan, is my understanding of wabi-sabi.

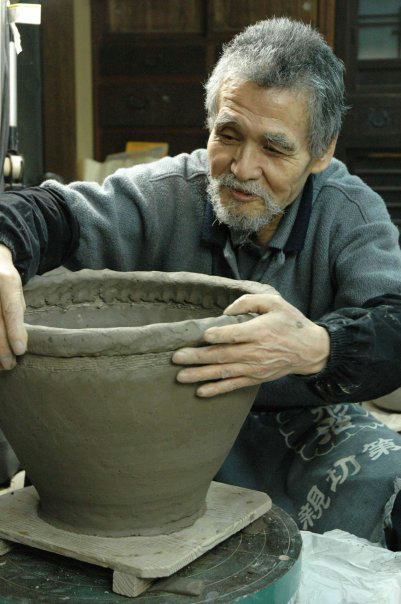

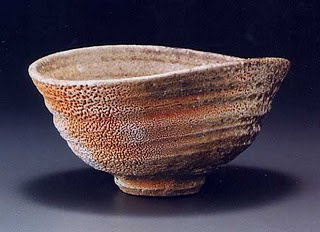

I traveled to Shigaraki, an ancient pottery center, to visit Buddhist priest and Tea master Shiho Kanzaki. Kanzaki-san’s exquisite vases, pots, and tea bowls, fired in traditional wood-fired Anagama kilns, embody wabi-sabi’s very essence.

Over lunch with Kanzaki-san and his wife in a weathered Shigaraki teahouse, we stopped before each course to admire the pottery. The bowls and plates had been made by Kanzaki-san’s apprentices, and he quietly pointed out the color variations and the markings left by ash when the dishes were fired. We admired how the rustic acorn-colored bowls embraced lightly battered shrimp and soba noodles as steam rose from the thick dark cups holding our strong green tea.

He turned the conversation to relationship. “Manner and behavior is most important,” Kanzaki-san told me. “You always have to think of other persons. If you are always thinking of other persons, you can understand the real wabi-sabi.”